| Project Premises : Artist Talk : Credits : Feedback |

Artist Talk :: |

|

:: Living Landscapes

Walkers : Land : Water : Objects : Crosses : Hope ::

|

El Guadalupano |

Delilah: The Arizona-Sonora border is a contemporary cultural landscape. I see it as a middle passage, a contemporary middle passage. It's a grey zone and I think it's one that really deserves our attention.

Orlando: When I first saw Delilah and her work, it was at an Intro to Chicano Studies course that Yvonne and Renato Rosaldo were teaching at Stanford. I was really struck by her image of Guadalupe on the prisoner. And that stayed in my mind. I was drawn by the idea of reorganizing reality through digital media. I think that it creates another form of truth. So when I went to Houston and found out that Delilah was there, I decided I wanted to take a class with her but it turned out we had this opportunity to do a project in what's called Fotofest. And of course this has been an obsession of mine - the border and migration - for a long time. So I jumped at the chance.

|

Humane Borders Map 2003 |

But to get back to the idea of the landscapes and cultural landscapes at the Arizona border, this is a map from an organization called Humane Borders. They go out and put water stations in the desert and those blue flags are the water stations. Each station has about two or three 50-gallon tanks. And the red dots are the areas where people have died crossing the border through exposure, mostly. The orange area is the Tohono O'Odham reservation. The other half of the reservation is down in Mexico. That's another history of colonization and it's created really bizarre results. This project is called the trail of thirst but obviously there are millions of trails that people follow. There's a town about 60 miles below the border town of Sasabe called Altar where people go and gather to find a coyote who then takes them to one of the border towns. Once they start walking, they can cover about 25 miles or so in one day, maybe 10 miles walking and the rest of the time stuffed in a van.

Usually they'll get somewhere around this station  . The next day they can get another 25 miles or so and they can get to right below those red dots where there's a huge concentration of deaths. On the third day, they'll usually get around where we took our last set of images. That's usually the pickup point

. The next day they can get another 25 miles or so and they can get to right below those red dots where there's a huge concentration of deaths. On the third day, they'll usually get around where we took our last set of images. That's usually the pickup point  where people kind of disrobe, take off the clothes that they used trying to get there and put on the new clothes if they managed to bring some along.

where people kind of disrobe, take off the clothes that they used trying to get there and put on the new clothes if they managed to bring some along.

|

Photo by Delilah Montoya |

Delilah: When this was still in the planning stages, one of the reasons I got inspired was that FotoFest which is a biennial event, an international event, that Houston brings. People come from all over the world and also all over the country. So it was going with the theme of water and when I began to talk to Orlando about what he was doing along the border, I thought this was perfect Fotofest material. To create a kind of documentation, but what I was really interested in was the fact that Orlando was from Houston. And also, about the same time we saw Victoria happen.

Orlando: That happened in 2003. There were about forty-four people in a cargo container in the back of a semi. And this truck was found a few miles south of Houston in a town called Victoria. I think 18 people were found that had died of asphyxiation. Casa Juan Diego.org has personal narratives of the happening.

Delilah: Houston's hot, so if you put forty people in the back of a semi and drive through Texas, they're going to suffocate. And pendejos, this guy did. And he wasn't attentive. They were trying to get out of there. They were trying to get his attention and he just kept on driving. And before he realized it and his semi is rocking because people are trying to get out, when he opened it up, he saw that about eighteen people had already died.

Orlando: And then the guy ran. Just now they're starting to put some of those people in jail.

Delilah: So it was part of why we felt we needed to make a statement during Fotofest about what was going on there, particularly with the issue of water. And so basically what I did was to try and bring the issue to a fine art place, one that would have a high visibility at that particular time. We had to find a venue and Orlando found a place at Talento Bilingüe de Houston. What we wanted to do was bring the show to the community because most of the mexicanos in Houston have made that passage, have gone through that middle passage. And Orlando too, that's part of your experience, that's part of your family story.

Orlando: When we were at the opening and my dad was there, he was telling me. You know when I first got here, the first time like in 1979, it was about two or three blocks from here and that's were we first arrived. Three blocks from were we had the actual show.

|

Photo by Delilah Montoya |

Delilah: That was pretty amazing. The other thing that I did was a little bit of the homework. I made sure that we had public relations out there. If we were going to make this an issue that people could begin to talk about, we had to get the media. We were able to get TV, a magazine picked up the article, the newspaper picked it up and also it got picked up on television, one of the stations picked it up and did an interview with us.

Orlando: That photo was taken in the Tohono O'odham reservation  , right below that large concentration of deaths that happened in 2003. You can probably tell that those jugs probably weren't arranged so perfectly out there. We put them up.

, right below that large concentration of deaths that happened in 2003. You can probably tell that those jugs probably weren't arranged so perfectly out there. We put them up.

Delilah: No they weren't. I'm the artist.

|

Placing Jugs by Mario Arosemena |

Orlando: Those jugs are from a Tohono O'odham reverend named Mike Wilson  . One thing I didn't point out is that you'll notice there aren't any water tanks in the Tohono O'odham reservation and that's because they are kind of conflicted about whether or not they want to put water tanks out there. Some of the people in the community feel it would encourage more migration. Some of them feel that the immigrants and the drug traffickers are moving in the same place. They're more afraid of the drug traffickers, but it's a controversial issue.

. One thing I didn't point out is that you'll notice there aren't any water tanks in the Tohono O'odham reservation and that's because they are kind of conflicted about whether or not they want to put water tanks out there. Some of the people in the community feel it would encourage more migration. Some of them feel that the immigrants and the drug traffickers are moving in the same place. They're more afraid of the drug traffickers, but it's a controversial issue.

Delilah: They're also very afraid of the amount of people that are coming through. Because we're not talking about a couple hundred people, we're talking about thousands of people that are coming through.

Orlando: I think the number is fifteen hundred people per day. This is according to the tribal police in the Tohono O'odham nation. I don't know what the population of the reservation is but within a month if all those people were to stay, it would exceed it. So what Mike Wilson does is to go out and put water out in the reservation and he was kicked out of the reservation for doing this. But he still goes there to do it.

Delilah: The tribe really does not want the water jugs out there. They're afraid more people could come through but on the other hand people are dying. So how do you understand your humanity at this point? Do you allow the migrants to die of lack of water? And so certainly Mike made a decision that he couldn't live with himself knowing people were dying out there.

|

Photo by Delilah Montoya |

Orlando: One way that people find their way is to follow the power lines. And this leads to one of those pick-up sites. Once people get there, they disrobe, they get rid of their clothes and if they have newer clothes they put that on. I'd imagine that it's so when they go to the airport or wherever they're going they don't look like they just crossed the border.

|

Photo by Delilah Montoya |

Delilah: The other thing is that there is a real feeling of the presence of absence. You feel as though some body was there. You feel the absence of that person. In order to suggest that one of the things that I did of course digitally was to throw a shadow in there, just the shadow and not the person. Just to kind of suggest that absence.

:: Baboquivari Water

Walkers : Land : Water : Objects : Crosses : Hope ::

Orlando: One of the things that sociologists and anthropologists try to do is say why are people coming? Why are they risking their lives to do this? And what does this mean today? And one of the reasons I called it the trail of thirst was to allude to the Trail of Tears, a historical moment when indigenous people were forced off of their land. In the current moment of neo-liberal policies, of NAFTA and the privatization of land in Mexico, there is another forcing of people off of their land and these also tend to be indigenous people who are also the poorest in Mexico with the least connections to the United States and the ones forced to go on this trail.

Delilah: And that peak there is actually a very important peak right.

|

Photo by Mario Arosemena |

Orlando: That's Baboquivari Peak  . But it's a very Chicano sort of idea to take something that happened to indigenous people in the past and to associate it with something that is happening today, but things are more complicated than that. So people in the reservation don't necessarily see the Oaxacan

. But it's a very Chicano sort of idea to take something that happened to indigenous people in the past and to associate it with something that is happening today, but things are more complicated than that. So people in the reservation don't necessarily see the Oaxacan  coming from Mexico as an indigenous person, they might see him as a Mexican. This peak, Baboquivari Peak, is an important location associated with a Tohono O'odham creation story, but it's also now become one of the other navigational landmarks. I mentioned the power lines, and then there's also this peak.

coming from Mexico as an indigenous person, they might see him as a Mexican. This peak, Baboquivari Peak, is an important location associated with a Tohono O'odham creation story, but it's also now become one of the other navigational landmarks. I mentioned the power lines, and then there's also this peak.

|

Mexican brand water label. |

But in the town Sasabe on the border, there's some Mexican entrepreneur saying I'm going to appropriate this image and I'm going to put it on my water bottle and I'm going to sell water. But it's misspelled. It's "Baboquiv..." So it's kind of a transculturation. There's a group called the Samaritans that goes out there and tries to give first aid to migrants that they see. And while I was with them, I saw this bottle  . And they had already told me about the whole creation story and about it being a navigation tool.

. And they had already told me about the whole creation story and about it being a navigation tool.

|

Photo by Orlando Lara |

So what I did was to associate that with the whole idea of water and thirst and the question of why are people coming? And so I created labels for the water bottles, listing some of the thirsts that drive people to migrate. One of the problems with the big sociological theories that I was talking about is that you lose the personal motivation, the actual reasons that people come. And these are some of the reasons that I have been able to draw from my experience, from my family. It could be a job opening up at this apartment complex, for a better place to live, or to even make enough money to make a place to live in Mexico. That's a big dream that people have too, not necessarily because they want to become United States American. It makes me mad when people have that assumption. So we put all these different issues of water and thirst together and created this installation piece  .

.

:: Discarded Objects

Walkers : Land : Water : Objects : Crosses : Hope ::

|

Photo by Orlando Lara |

Delilah: One of the things that we also did was, if you follow that trail, you're going to find things on the ground. And we started picking up all these items that we found. And at first look they look like trash. They look like somebody just discarded these things, but all of a sudden when you begin really focusing on what you've picked up, you realize that there's stories behind each and every one of those items. And we thought that it was very much a part of the experience. It's very much a part of the absence of the presence of a person.

|

Photo by Delilah Montoya |

So even those medallions. We just broke the bush off and someone had added all these medallions but they did it in such a way where it became a shrine. One night, they needed the shrine, they needed this for that moment and they left it behind. That always amazes me, what gets left behind. One of the people that we were working with, Beatriz, likes to take pictures of the rodeo, the Mexican rodeos in Houston  . And we were looking around and looking at all the backpacks. And the first one she picks up is a vaquero's backpack.

. And we were looking around and looking at all the backpacks. And the first one she picks up is a vaquero's backpack.

Orlando: It had the Resistol Jeans and the muscle relaxation cream  for the bull riders.

for the bull riders.

Delilah: All of that right, so there was a bull rider that was trying to come across the border. But then the question becomes, why did he leave those big jeans behind, his medicine, all of that just got left behind.

|

Photo by Mario Arosemena |

Orlando: There's this whole tracking that goes on, that the Border Patrol does and also that these humanitarian groups do while they're going out and filling up the water. They start tracking footprints with the idea that they want to have an encounter. They call it an encounter. And that just sounds like encountering ghosts. You use the same word. The picture was taken by a friend from Tucson, Mario Arosemena.

Delilah: Actually he became our guide. He's the one that got us through these trails because we would have never been able to find them alone.

|

Photo by Orlando Lara |

Orlando: I found this ID card while I was driving to one of the border towns, Douglas, AZ. That's in a region that is really infamous for rancher vigilantes but I was driving down the rode getting there and I could see these group of migrants sort of peaking out from the side of the road waiting for the road to clear so they could run across. I drove a little bit further and then I don't remember exactly how it happened but I stopped. I scared them or something. I don't remember exactly but the point is that at that location there was a barbed wire fence along the road and I crawled underneath it. And I walked around and I saw this Mexican ID  on the ground. And it's from this guy that's eighteen years old, and I don't know why he would have dropped it or why it would have been found alone. But one of the things you do when you cross is that you take as little personal identification as possible. So if you get caught, you don't get in the system. So I imagine that maybe he wanted to hide his identity or maybe he just dropped it.

on the ground. And it's from this guy that's eighteen years old, and I don't know why he would have dropped it or why it would have been found alone. But one of the things you do when you cross is that you take as little personal identification as possible. So if you get caught, you don't get in the system. So I imagine that maybe he wanted to hide his identity or maybe he just dropped it.

|

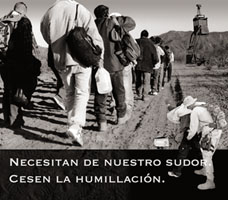

And Apprehension |

I found it next this portable observation tower  . The activists call them cherry pickers, but it's just another technology of surveillance. It's really useless. Most of the time, they're empty. There was nobody in there. One day, I went on a trip with a group called BORSTAR , a kind of PR, the humanitarian wing of the Border Patrol. They're in charge of trying to save people's lives, if they can, and then, of course, deporting them. So here these men are really just under unnecessary surveillance.

. The activists call them cherry pickers, but it's just another technology of surveillance. It's really useless. Most of the time, they're empty. There was nobody in there. One day, I went on a trip with a group called BORSTAR , a kind of PR, the humanitarian wing of the Border Patrol. They're in charge of trying to save people's lives, if they can, and then, of course, deporting them. So here these men are really just under unnecessary surveillance.

Delilah: This is a group that just got caught.

|

Photo by Orlando Lara |

Orlando: Most of these guys were from Oaxaca  . And one of the guys was telling me, what are you doing here? Why can't you tell people in the United States that we just want to come work? We don't want to ask for anything. We just want to come work. Why do we have to come this way?

. And one of the guys was telling me, what are you doing here? Why can't you tell people in the United States that we just want to come work? We don't want to ask for anything. We just want to come work. Why do we have to come this way?

Delilah: You see everybody carrying these water jugs. The jugs are basically survival to get through that desert.

|

Sed y Sudor |

Orlando: That's were it becomes a repeated image. The jugs. Of course the Border Patrol does this whole search ritual before they put them up on the bus to check to see if they have knives.

Delilah: I really like that naturalization that's up there.

Orlando: The INS isn't called the INS anymore; it's called ICE now. I don't know what it stands for. Part of the idea is that you're supposed to be able to become a citizen but it's so blocked for Mexican people. So I completed that sentence by calling it "and apprehension  ."

."

:: Saguaro Crosses

Walkers : Land : Water : Objects : Crosses : Hope ::

Orlando: The second issue for me is the problem of border deaths, but I wanted to come up with an image that really talked about it strongly. Something that I saw Humane Borders had put up in a kind of outside booth area was a newspaper story  that the Arizona Republic had published in 2000 where it told all the stories as far as they could research of the 205 people who had been found dead in Arizona that year. These are some of the stories.

that the Arizona Republic had published in 2000 where it told all the stories as far as they could research of the 205 people who had been found dead in Arizona that year. These are some of the stories.

"February 12 - Elia Perez Ramirez, 38. Puebla. Five skulls and incomplete skeletons were located at the base of the Black Mountains south of Ajo, scattered over 300 yards. Investigators found a sweatshirt with an embroidered U.S. flag, a tattered Tweety Bird sock, a prayer card, eye shadow and an envelope that said, 'I love you, son,' in Spanish."

"July 21 - Jane Doe, 37. Ofelia Maria Garcia-Chavaloc, 26. Two women were found together on the Tohono O'odham Reservation. Garcia-Chavaloc's long, dark hair was pulled back in a purple tie. Jane Doe was 4 feet 11. Her black T-shirt said "Realismo Fashion Girls."

An Arizona Spanish teacher was actually riding along with the Border Patrol when these two women were found and she documented their story. And so one of the changes that is happening now is that more young women and adolescents are crossing the border.

|

Digital Scan by Orlando Lara |

Delilah: It's actually a very young population that's coming across that border. When we looked to see the things that were being discarded, the type of food that they were bringing with them: white bread, candy, canned tuna. We found mayonnaise, mayonnaise across a border, no refrigeration? These aren't necessarily foods that one takes on a three-day hike. You're looking at foods that got picked up very quickly. So what's getting them across is not necessarily a good diet, its just pure drive, motivation, to make that three-day walk. I know what was really heart breaking was when we found a boy's shoe, maybe a six-year-old. And the heels were just broken off. A little six-year old making a three-day walk like that.

Orlando: You can see right there in the numbers how the deaths have been climbing. And now since the past five years, forty-four percent  of the deaths have been happening in that Tucson area and a huge amount of that is happening in the Tohono O'odham reservation.

of the deaths have been happening in that Tucson area and a huge amount of that is happening in the Tohono O'odham reservation.

Delilah: That's why that area is so critical. The reservation is sovereign country. So that means that the Border Patrol can't get in there unless they get the permission of the tribe and the tribe doesn't want to be patrolled. But on the other hand they don't want water out either. So it just makes a real dire situation.

Orlando: I think that's one area where the sovereignty that Native American communities have kind of breaks down. The Border Patrol does go in there and they went with me in there. But one of the things I remember them saying is that, when we come in here, we really think that people are helping people across. That was their idea. The agents I was with said they've found a lot of people hiding in people's houses. They have a kind of cynical take on it. They think some people are trying to make some extra money out of it, that they're charging migrants to let them stay.

Delilah: So they believe there's entrepreneurship going on?

|

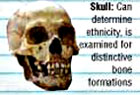

The Arizona Daily Star |

Orlando: Those numbers that I gave you, I want to complicate them a little bit with the technologies that they actually use to identify bodies. It's the county examiners that examine the bodies and they look for these different items that people have in order to identify them. What I wanted to really point out here is the skull  . It says here they can determine ethnicity if they examine for distinctive bone formations. But forensic anthropologists and geneticists are saying that race doesn't exist, that there's no biological meaning to it but then at the same time you have these forensic anthropologists saying that it does here. And now genetic biologists are also using DNA to find genetic ancestry and things like that.

. It says here they can determine ethnicity if they examine for distinctive bone formations. But forensic anthropologists and geneticists are saying that race doesn't exist, that there's no biological meaning to it but then at the same time you have these forensic anthropologists saying that it does here. And now genetic biologists are also using DNA to find genetic ancestry and things like that.

Delilah: It's kind of interesting, they have this website where you can put in identification of somebody that you're looking for to see if they can find the forensic evidence that they had died. The only thing is it's all in English.

Orlando: Reuniting Families.org is an interesting project out of Waco, Texas. These forensic anthropologists have all this data on people who have been found. You can go in there and type information on someone you think you've lost. They send you a DNA kit and you take a cheek swab and you mail it back and then they'll tell if there's a match. I mean they've been able to help people that way at least to figure out what happened to their family. But as of now it's easier for people who are living in the United States and were waiting for somebody to come back.

|

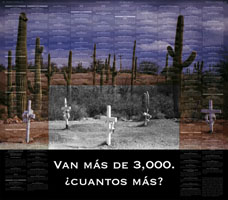

Photo by Orlando Lara |

This is an image right outside of Altar, the place where people come to gather. Right outside of it there is this fifty-mile dirt road that takes you to Sasabe. Right at the beginning there's this huge warning that's really directed at the immigrants telling them how many people have died. It's obviously too late. By the time you're there you're going. You have people waiting for you. You're not going to turn back. And you also don't really know what the dangers are or you don't believe it.

I found this image of a tribal cemetary  also in the reservation. There are many John Does there. I don't know if they are actually migrants but for me just the symbolism of the crosses and the saguaro cactuses that look kind of like crosses is very powerful. So this is the image that I created out of that.

also in the reservation. There are many John Does there. I don't know if they are actually migrants but for me just the symbolism of the crosses and the saguaro cactuses that look kind of like crosses is very powerful. So this is the image that I created out of that.

|

¿Cuantos Más? |

Delilah: It has all the intonations of those that had died, the question that was asked of them at Altar.

Orlando: It's more now. This is the actual number as of now. And the question is also directed at the United States, to people in the United States, "How many more until this becomes a critical issue?"

The reality is that there are more than 3,000 people that have died since 1996 and Operation Gatekeeper but there's a lot more that have gone through. A lot more.

Delilah: Many make it.

:: Hope and Dignity

Walkers : Land : Water : Objects : Crosses : Hope ::

|

"They're like the person was just lifted away..." |

Orlando: So about ninety percent of the people that try make it. So I'm trying to bring in a sense of hope that I think you can see in the things that people leave. These shoes were left out there like that. This lady, Leslie Beach of the Samaritans the group that goes out to try to give aid, this is what she said about it, "they're like the person was just lifted away, hopefully to a better life." That comment just stayed with me. And then some of the items that we did bring back, these are some close-ups of them: the card, the phone number  , which is sometimes the only document that people are found with. That phone, it could be the family, it could be the next level of the coyote that you need to go to. All I know is that the area code leads to Ubadilla, New York.

, which is sometimes the only document that people are found with. That phone, it could be the family, it could be the next level of the coyote that you need to go to. All I know is that the area code leads to Ubadilla, New York.

Delilah: It could not even be anybody on that other line.

|

Digital Scan by Orlando Lara |

Orlando: That's your lifeline. And then we found a ribbon, "Fe y Esperanza," which comes from something called La Antorcha Guadalupana. It's this peregrinación that Mexican migrants and immigrants have organized from La Basilica in Mexico City all the way to New York. So somebody had this and left it. And also there's a huge community of Poblanos in New York. These are some other items, just cologne  . Somebody wanted to smell good.

. Somebody wanted to smell good.

Delilah: We're looking at a very young population that's concerned with smelling good after that walk.

Orlando: These are huaraches  . See how they're all worn.

. See how they're all worn.

Delilah: All the way down.

|

Digital Scan by Orlando Lara |

Orlando: And that's a little shoe. That's a little bitty shoe.

Delilah: That's probably about an eight-year-old's shoe right there.

Orlando: These are some other items. We imagine that they come from a girl that's about sixteen or eighteen years old. She decided she was going to walk across the desert in heels.

Delilah: Much of the population is ill prepared for that walk. There is no concept of what it is they're walking across. In my estimation, they're probably coming out of urban areas. Because if they came out of a rural area, they would know what a three day walk through the desert would be and these are not shoes that you want to walk through the desert for three days. And you see a lot of shoes like that. You see a lot of items like that.

|

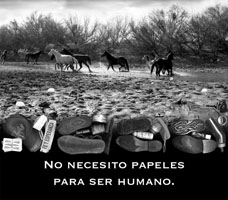

Para ser Humano |

Orlando: This location is that zone in the reservation where all those red dots are. When I was out with BORSTAR , they took me there because of that. I was with a Mexican American Border Patrol guy and this white lady from somewhere in the Northeast. They were both around twenty-eight. The first thing I saw were these horses  running around. But about fifty meters away, the lady told me a story. They have all these experiences about coming across these bodies. So it's kind of traumatic I would think to have their job. But she was telling me about when they found a brother and sister. The brother had survived and had gotten a can of tuna

running around. But about fifty meters away, the lady told me a story. They have all these experiences about coming across these bodies. So it's kind of traumatic I would think to have their job. But she was telling me about when they found a brother and sister. The brother had survived and had gotten a can of tuna  there and used it to carve out a hole in the sand. And his sister had already died. And it felt to the lady like he was... her story was that he was kind of getting delirious. He was in that moment of no hope where you feel like this is the end and he'd been digging a grave for themselves. But then I come across these horses, just kind of alive, running around free. And putting all that together, this is what it meant to me, this idea that "No necesito papeles para ser humano - I don't need papers to be human." For me the biggest violation that's happening in that zone, in this social context, is that the rules of what it means to be a human are so inverted that these horses, these animals are freer to move and be alive than people. That for me is the biggest violation.

there and used it to carve out a hole in the sand. And his sister had already died. And it felt to the lady like he was... her story was that he was kind of getting delirious. He was in that moment of no hope where you feel like this is the end and he'd been digging a grave for themselves. But then I come across these horses, just kind of alive, running around free. And putting all that together, this is what it meant to me, this idea that "No necesito papeles para ser humano - I don't need papers to be human." For me the biggest violation that's happening in that zone, in this social context, is that the rules of what it means to be a human are so inverted that these horses, these animals are freer to move and be alive than people. That for me is the biggest violation.

Delilah: The response that we got from the community was very strong. It was what I was hoping for. When we were putting up the installation at Talento, the woman who was cleaning the area, obviously a mexicana. She sees what we're doing and she asks, "This is about the border crossing isn't it?" Immediately, she knew what it was, and then that mariachi, he walked through and then all of a sudden he stops and asks what is it? It's in Arizona, we say. "There's another one in Laredo," he responds. Immediately, the community knew what it was. It was something that everybody knew. It was an unspoken word that now at this point they could begin to speak about it. And that's what we wanted. We wanted the community to begin talking about and experience what had been veiled, not to be spoken.

Student: Do you know where the conversation is at now in the reservation?

Orlando: No, I don't know. I want to do more research on that but I don't even know if it's an issue that I really want to get into. But one thing I have thought about. One ideal place to exhibit a work like this would be in the reservation. I would like to do that. Because to me, that's one of the powers that art has. Art can create dialogue where there is silence. Or controversy, sometimes it can stir up controversy and that can be good too.